© Sick House Finch by Tamami Gomizawa

Vous pouvez nous aider à suivre l’évolution de la maladie en participant au Recensement des Roselins familiers et des Chardonnerets jaunes touchés par la conjonctivite

La conjonctivite a été rapportée pour la première fois en 1994, à Washington D.C., par des participants du Projet FeederWatch. Les oiseaux infectés se reconnaissent par leurs paupières rouges, enflées et croûteuses. Ils peuvent également rester de longues heures sans bouger, essayant de temps à autre de se gratter les yeux avec leurs pattes ou encore, de se frotter la tête contre un arbre, maladroitement. Dans les cas extrêmes, les oiseaux deviennent incapables d’ouvrir les yeux et ainsi subvenir à leurs besoins. Bien que certains réussissent à guérir, nombreux sont ceux qui meurent de faim, de froid ou deviennent la proie d’un prédateur.

La conjonctivite chez le Roselin familier peut être causée par plusieurs facteurs, mais, dans la plupart des cas, elle est le résultat d’une bactérie appelée Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Les chercheurs ont depuis longtemps identifié cet agent pathogène chez le dindon domestique et le poulet, mais c’était la première fois, en 1994, que la bactérie était notée chez une autre espèce. Cependant, de récents rapports semblent indiquer que le Chardonneret jaune serait lui aussi touché par la maladie. Le regroupement des oiseaux aux mangeoires est sûrement un facteur qui facilite la transmission de cette maladie.

Vous pouvez nous aider à suivre l’évolution de la maladie en participant au Recensement des Roselins familiers et des Chardonnerets jaunes touchés par la conjonctivite. Pour plus d’information, visitez le site Internet consacré au recensement ou communiquez avec le personnel du Projet FeederWatch à pfw@bsc-eoc.org

About the disease (en anglais)

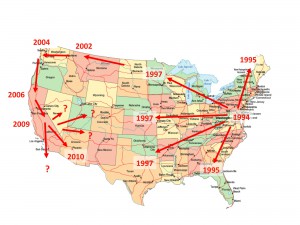

Since January 1994, when House Finches with red, swollen eyes were first observed at feeders in the Washington, D.C. area, including parts of Maryland and Virginia, House Finch disease has spread rapidly through the eastern House Finch population. Mycoplasmal conjunctivitis, as the disease is commonly called, is caused by a unique strain of Mycoplasma gallisepticum, a parasitic bacterium previously known to infect only poultry.

To date, the House Finch eye disease has affected mainly the eastern House Finch population, which is largely separated from the western House Finch population by the Rocky Mountains. Until the 1940s, House Finches were found only in western North America. They were released to the wild in the East after pet stores stopped illegal sales of “Hollywood Finches,” as they were commonly known to the pet bird trade. The released birds successfully bred and spread rapidly throughout eastern North America. Since 2006, however, the disease has crossed the Rocky Mountains and started popping up in western states; the question now is, how much has it spread in the west?

Will Mycoplasma gallisepticum eventually cover the entire North American House Finch range? If so, at what rate will the epidemic continue to expand? Will House Finch numbers decrease in the West as they have in the East? Will other bird species become infected with the conjunctivitis? Data from Project FeederWatch participants will help us find out.

History of Research (en anglais)

Starting in 1994, because of the efforts of participants across North America, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology started the House Finch Disease Survey. This survey collected data on the spread and prevalence of a bacterial disease that now affects House Finches from the Atlantic to Pacific coasts. These data have been invaluable for documenting the spread of the disease and have motivating research that seeks to understand the reasons for persistence of the disease as well as its longer-term impact on House Finch abundance.

In 2008, the House Finch Disease Survey ended as a stand-alone project, but monitoring the disease continued through the data collection protocol in Project FeederWatch. Now, in 2013, biologists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology are renewing efforts to collect data on this disease because it is continuing to spread to new areas of North America.

We have modified the data collection method within the FeederWatch protocol to allow for more accurate information about the presence and absence of the disease, and we are actively encouraging all FeederWatchers to look for signs of the disease in their own house finches and report whether they see it or not. Importantly, looking for the disease and NOT seeing signs of it is as valuable to report as observations of disease presence. See our recent blog post here

Recognizing Conjunctivitis (en anglais)

Nous nous excusons, mais cette page n’est présentement pas disponible en français

Birds with avian conjunctivitis often have red, swollen, watery, or crusty eyes; in extreme cases the eyes are so swollen or crusted over that the birds are virtually blind.

Avian pox is another disease that affects House Finches. This disease is characterized by wart-like growths on the featherless areas of the body such as around the eye, the base of the beak, and on the legs and feet. Avian pox can be mistaken for conjunctivitis when the eyes are affected. “Growths” on the eye are typically from avian pox.

Useful links (en anglais)

Nous nous excusons, mais cette page n’est présentement pas disponible en français

Learn how to distinguish House Finches from the similar Purple Finch and Cassin’s Finch on our Tricky Bird ID page.

Learn more about House Finch biology on the All About Birds page.

Learn more about the disease spread on the All About Birds Blog.

Frequently asked questions (en anglais)

Nous nous excusons, mais cette page n’est présentement pas disponible en français

Seen a sick bird and want to report it?

Participants in Project FeederWatch can provide their observations of diseased House Finches in their standard count entry procedure. It is especially important for people to report if they look for the disease but don’t see house finches with apparent infection. This means checking the “yes” box when asked if you looked for the infection, and typing in a “0” when asked how many finches were infected. You may think zeros are boring, but they are not! In order to track the spread of any disease, we need to know where is occurs, but also where it does not yet occur.

What does conjunctivitis look like?

Infected birds have red, swollen, runny, or crusty eyes; in extreme cases the eyes become swollen shut or crusted over, and the birds become essentially blind. Birds in this condition obviously have trouble feeding. You might see them staying on the ground, under the feeder, trying to find seeds. If the infected bird dies, it is usually not from the conjunctivitis itself, but rather from starvation, exposure, or predation as a result of not being able to see.

Do other diseases cause similar clinical signs?

Avian pox is another common disease that affects a bird’s eyes. This disease causes warty lesions on the head, legs, and feet, but cannot always be easily distinguished from conjunctivitis. Avian pox is transmitted by biting insects, by direct contact with infected birds or contaminated surfaces (e.g. feeders), or by ingestion of contaminated food or water. Just as with conjunctivitis, the infected bird becomes vulnerable to predation, starvation, or exposure.

What causes the conjunctivitis?

Although infected birds have swollen eyes, the disease is primarily a respiratory infection. It is caused by a unique strain of the bacterium, Mycoplasma gallisepticum, which is a common pathogen in domestic turkeys and chickens. The infection poses no known health threat to humans, and had not been reported in songbirds prior to this outbreak. Researchers at various institutions are currently trying to learn more about the transmission, genetics, and development of this disease.

Where did the disease start? How far has it spread?

Conjunctivitis was first noticed in House Finches during the winter of 1993-94 in Virginia and Maryland. The disease later spread to states along the East Coast, and has now been reported throughout most of eastern North America, as far north as Quebec, Canada, as far south as Florida, and as far west as California. It has also appeared in some species other than House Finches. Your participation in Project FeederWatch will help document further changes of this epidemic.

What other bird species have been diagnosed with Mycoplasmal conjunctivitis?

So far, the disease is most prominent in the House Finches. However, a few reports of the disease have been confirmed in American Goldfinches, Purple Finches, Evening Grosbeaks, and Pine Grosbeaks, all members of the family Fringillidae.

Why might eastern House Finches have been the earliest victims of the disease?

House Finches are not native to eastern North America. Until the 1940s, House Finches were found only in western North America. Some birds were released to the wild in the East after pet stores stopped illegal sales of “Hollywood Finches,” as they were commonly known to the pet bird trade. The released birds successfully bred in the wild and spread rapidly throughout eastern North America. Because today’s eastern House Finch populations originated entirely from a small number of released birds, they are highly inbred, exhibit low genetic diversity and, may therefore be more susceptible to disease than other bird species native to the East.

Why has the disease spread so rapidly among House Finches?

The House Finch population is large, and the birds tend to move together in highly mobile foraging flocks. Therefore, diseased individuals are constantly entering new areas, increasing the chance of infecting other birds in that area. Also, some infected birds do not die from the disease, which increases the probability of its transmission to other individuals. Lastly, current evidence suggests that infected birds do not acquire immunity to future infections.

Do bird feeders encourage the spread of conjunctivitis?

Whenever birds are concentrated in a small area, the risk of a disease spreading within that population increases. Even so, feeding birds may not necessarily increase the rate of disease spread, and should not have a net negative impact on the House Finch population. House Finch Disease Survey data tell us that the disease has decreased from epidemic proportions and is now restricted to a smaller percentage of the population. We estimate that 5% to 10% of the eastern House Finch population has this disease and that the dramatic spread that occurred a few years ago has equilibrated. This means that it is still an important and harmful disease, but that House Finch populations are not currently at extreme risk of wide-spread population declines.

Nonetheless, please be responsible and clean your feeders on a regular basis even when there are no signs of disease.

What should I do if I see a bird with conjunctivitis?

Take down your feeders and clean them with a 10% bleach solution (1 part bleach and 9 parts water). Let them dry completely and then re-hang them. Also, rake underneath the feeder to remove old seed and bird droppings.

Should I try to treat an infected bird?

By law, only licensed professionals are authorized to handle most wild birds. Although it is possible to treat finches with conjunctivitis, you should not add medications to bird seed or baths under any circumstances. There is no way to know if medication actually helps birds in uncontrolled conditions, and such treatment may in fact contribute to disease spread by allowing infected birds to survive longer. Treatment with antibiotics may also lead to the rapid evolution of novel strains of the disease that could possibly spread to other songbirds.

Bird-Feeding Guidelines:

Space your feeders widely to discourage crowding.

Clean your feeders on a regular basis with a 10% bleach solution (1 part bleach and 9 parts water) and be sure to remove any build-ups of dirt around the food openings. Allow your feeders to dry completely before rehanging them.

Rake the area underneath your feeder to remove droppings and old, moldy seed.

If you see one or two diseased birds, take your feeder down and clean it with a 10% bleach solution.